The intellectual commons have been poorly governed for a long time. Perhaps always. The particulars of poor governance have varied over the decades, centuries and millenia, depending on the structures of society and technologies over the decades, centuries, and millenia. But the rise of digital networks has opened up a new world of possibilities for creative and cultural freedom. Social interactions in theory restricted by copyright law (a major source of commons malgovernance for centuries) have exploded, unleashing new sorts of social, democratic, and economic value-creation.

The legal and policy response of established content industries – film, music, publishing, information – has generally been to ignore the intellectual commons, and sometimes to attack it. Over the past two decades, it has retroactively extended the terms of copyright law, preventing works from entering the public domain; shrunk “fair use” and other exceptions that allow re-use of copyrighted works without permission or payment; created new copyright-like monopolies; waged mass lawsuits against ordinary people; suppressed technologies that enable mass sharing; and expanded the geographic scope of copyright regimes.

Commoners develop the tools to build their commons

The most exciting governance developments for intellectual commons have come not from the legal establishment, public policy or business, but from hackers and activists. Over the past twenty years they have carved out new practices, technological tools and legal affordances to help them build, maintain and protect their intellectual commons. The free software movement led the way in the 1980s, not long after copyright law began to apply to software. By the late 1990s, many creators, particularly those using the Internet, wanted to invigorate the commons of culture, education, and science using similar means. From this milieu Creative Commons (CC) was launched in 2002.

There were many pre-CC attempts to fashion public licenses that would help govern intellectual commons beyond software. These included the Free Documentation License (FDL), Open Content Principles and Open Publication licenses, Open Audio License, Open Music licenses, Open Directory License, Public Library of Science Open Access License, Electrohippie Collective’s Ethical Open Documentation License, Free Art License, and others.

The support and public visibility of CC’s initial patrons and founders raised the profile of the nascent movement to build voluntary commons and not coincidentally, contributed to a more centralized stewardship of the tools used to build various commons. Some digital creators started using and recommending CC licenses instead of their own. Others moved their projects to CC licenses equivalent to their existing ones. The stewards and most significant users of remaining licenses often tried to make their licenses more legally compatible with one of the CC licenses, or migrate their works to them, in order to foster a greater interoperability of everyone’s content.

CC Licenses and Public Domain Tools

The first four tools here are fully free/libre/open – they permit any use by any user. |

| Public Domain Mark: for tagging works not restricted by copyright, e.g., because they are very old. |

| CC0 public domain dedication: copyright restrictions removed to the extent legally possible. |

| Attribution: any use by anyone permitted so long as credit is given. |

| Attribution-ShareAlike: same as previous, with additional condition that published adaptations must be offered under the same license. |

| Attribution-NonCommercial: any use not for commercial purposes permitted so long as credit is given. |

| Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike: same as previous, with additional condition that published adaptations must be offered under the same license. |

| Attribution-NoDerivatives: any use without modification permitted so long as credit is given. |

| Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives: same as previous, but not for commercial purposes. |

Central stewardship and commons interoperability

Centralization sounds bad. However, it is one way to address two of the biggest challenges to successful governance of an intellectual commons. The first challenge is how to assure the legal interoperability of content using different public copyright licenses. Lots of licenses and license stewards tend to produce a fractured commons with incompatible pools of content. Indeed, nearly all pre-CC licenses are incompatible with each other. This means that for a work published under one license, an adaptation cannot be published under another license, because the terms of the first license may not be fulfilled when the adaptation is offered under the second license.

For software, there are several important license stewards, and many licenses. The problem of interoperability has been partially solved over the decades through the primacy of one steward, the Free Software Foundation (FSF), and its General Public License (GPL). The FSF is the most experienced steward, and its strong commitments to the full freedom of software users (to copy, modify, re-use and share code) has assured transparency and predictability. Some other free software licenses are much more permissive than the GPL, making one-way compatibility (software under a permissive license may be incorporated into a project under the GPL, but not vice versa) a triviality. With other licenses, like the Apache Software License 2.0, great care was taken in crafting their legal provisions to align with the provisions of the GPL. The drafting processes accounted for the goal of compatibility (recipient and donor, respectively) between the GPL and Apache Software License, and provides an example of coordination in intellectual commons governance.

Freedom, commerce and the commons

Incompatibilities exist within the CC suite of licenses, by design. These are legal in nature, but also cultural and ideological. For example, may an intellectual commons discriminate against (and prohibit) commercial uses? One line of thought says no: Commerce is such a primary function of society that excluding commercial uses from the commons marginalizes the commons from society – and in any case, the copyleft requirement can force a public benefit from commercial uses (by requiring that the works be shareable and re-useable by others).

Think of commercially produced educational materials that adapt Wikipedia articles. Those commercially produced adaptations of Wikipedia materials must be shared under the CC Attribution-ShareAlike license (BY-SA), which means that others can freely copy and re-use them. Multiple other schools of thought disagree, however: Some creators want to exclude commerce from the commons. Another set of creators profess ignorance about what will be optimal for any given creative domain, e.g., photography, gaming, music, and therefore urge practitioners to figure out the best terms of governance within their respective domains. Yet another set of creators, in stark contrast with the first, may not wish to build non-commercial commons, but want to engage in traditional copyright-based commerce and refrain from granting commercial permissions while permitting non-commercial uses as a marketing strategy.

Debate about the best way to structure intellectual commons within different creative domains long preceded CC. For example, many of the early, non-software public licenses were not fully free/libre/open – that is, they don’t permit any use by any user. In the software world, this debate occurred years earlier as hackers questioned whether “free” should mean the freedom to re-use, modify and share for whatever purposes, or available at “no cost.” The ultimate consensus was that “free” should mean the former – or as FSF founder Richard Stallman memorably put it, “Free as in freedom, not as in free beer.” In 1991 Linux was initially released under non-commercial terms, but it soon switched to the GPL.

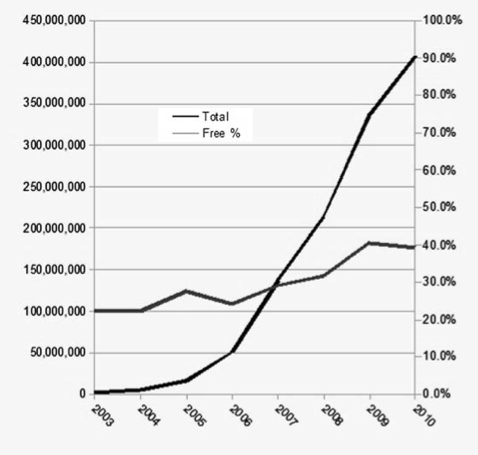

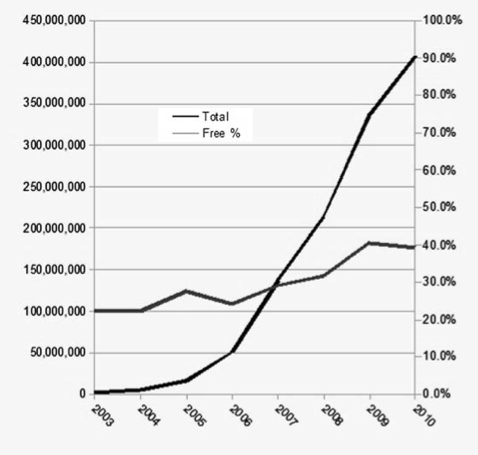

The free software world defined itself in terms of freedom quickly and decisively. The same definition might not be appropriate for other parts of the intellectual commons. However, it is also possible that permitting any user to make any use is a “sweet spot” of intellectual commons governance that other domains would have settled on without having free software as an example. Trends toward consensus for a “free as in freedom” standard can be seen in various non-software domains, including scientific communication (0pen access), learning (0pen educational resources), public sector information, data, and in aggregate statistics concerning the use of CC licenses. In 2003, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (BY-NC-SA) was by far the most popular license, surpassed by the fully free Attribution-ShareAlike (BY-SA) in mid-2009.

Creative Commons works at year end and percentage free/libre/open

Wikipedia and CC

The trend toward “free as in freedom” has been building for years. Attribution-ShareAlike’s (BY-SA) becoming the most popular license in the CC suite coincides with the migration of Wikipedia and other Wikimedia Foundation projects from the Free Documentation License, or FDL, to BY-SA as their primary license. This major shift marked the culmination of a relatively long chapter of modern, non-software intellectual commons governance. Wikipedia started in 2001, before the launch of CC licenses, and used the FDL, designed by the Free Software Foundation specifically for printed free software manuals. Hence FDL was not very appropriate for an online encyclopedia.

Many Wikipedians wished to migrate to BY-SA, but it was not that simple. Wikipedia relies on contributions being made under a public license rather than requiring contributors to grant rights to the site not also granted to the public. Incidentally, this is an intellectual commons governance best practice – a “more-than-equal” participant that does not have to play by the rules of the commons threatens the community’s cohesion and retards its self-governance. But the problem was that the FDL is not compatible with other copyleft licenses. Even if legal incompatibility were not an obstacle, it was not clear to many Wikipedians that CC would be the best steward of the project’s primary public license. CC’s less than fully free/libre/open licenses did not signal a serious enough commitment to non-discriminatory freedom. CC’s stewardship was also a concern of the FSF, the FDL’s steward, and the entity that would be needed to enable compatibility. As a result, Wikipedia’s migration to the BY-SA license has made the intellectual commons more interoperable and thus more robust and unified.

Public policy adopts CC licenses

The second challenge that centralized stewards of licenses help address is the visibility and credibility of the resulting commons. Through initial use by bloggers, photographers, musicians, and early institutional connections, CC licenses were able to gain mainstream publicity and validation; later adoption by software platforms and large institutions boosted usage to ever-higher levels. Many governments – Australia and the Netherlands stand out as pioneers – are now using CC tools to release public sector information. Funders are conditioning grants on the release of funded material under a public license, which guarantees at least some public benefit of access and re-use. CC licenses have become a standard means to create and participate in intellectual commons – and that, in turn, has made it easier for more commoners, including the general public, to participate in and benefit from the commons.

Another key to the visibility and credibility of CC licenses has been its worldwide network of affiliates (autonomous and located within existing institutions, e.g., law schools, cultural institutes, and Wikimedia chapters). These affiliates are key sources of expertise – and pressure – needed to optimize CC tools for worldwide use. Without this base, there would be more impetus for governments and others to create their own (incompatible) licensing tools, likely in ways that would fracture the commons.

In the fall of 2011, CC launched the process of gathering requirements for and drafting version 4.0 of its license suite. This will be another crucial (and long!) moment in the governance of the intellectual commons.

The future of intellectual commons?

Creative Commons and its colleague movements have re-opened the intellectual commons, which were until recently at best ignored. Now, they cannot be ignored. In many instances they out-cooperate intellectual monopolies in the marketplace as they demonstrate the non-market value of vibrant intellectual commons for culture, learning, science, democracy, and indeed the economy.

There are many open questions related to the governance of the intellectual commons and the appropriate structures for producing them. How do we avoid merely recapitulating proprietary methods, and instead utilize the characteristics of the commons to create works, products and commons that are more beneficial economically and politically?

Despite encouraging bottom-up developments, societal governance of the intellectual commons is still very poor. By comparison to the deep well of knowledge and experience concerning how to create and market intellectual monopolies, our knowledge and experience about commons-based peer production and governance of intellectual commons is puny. We can hope that history and technology are on our side and that the rise of the next generation will deepen our knowledge. Still, this will require much effort from the commoners to build the future that we need and want.

Buy at Levellers Press

Buy at Levellers Press